The ingredients that contribute to subsidence

- London Clay

- Water

- Trees

- Leaking drains

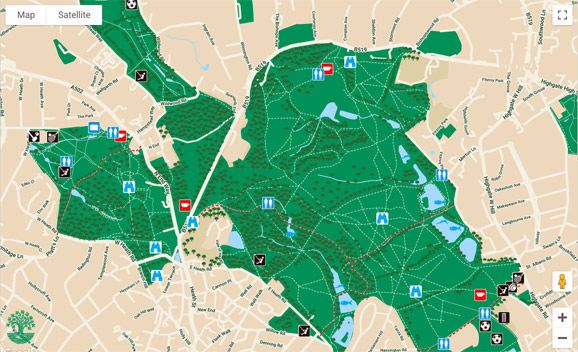

Trees however only have a ‘walk-on’ part: they do not contribute to subsidence without the primary role of water acting on clay first. Since they will be part of the solution and give us great pleasure, taking them out is not only an immediate waste of money, it means much more needs to be spent later when the true cause is discovered. Sadly, a ‘blame the tree’ culture, a lack of understanding of the true action of water on clay and trees, and an insufficiently strong legal protection for trees in situations where subsidence is occurring in the presence of trees, are all contributing to the gradual denuding of Hampstead’s magnificent canopy cover

Hampstead Geology

This part of the south east has a thick layer of marine ‘London’ clay laid down 60-50 million years ago when this area lay under a warm tropical sea. A layer consisting of a mix of clays, silts and sands – Claygate Beds – overlies the London clay, with a top layer of sand deposited by the enormous Bagshot river that ran from west to east across the whole of Wessex 50 million years ago.

Hampstead is on the top and southerly slopes of one of London’s sandy hills. These hills remained after glacial melt water from the last ice ages washed away much of the surrounding areas down to the London clay. The top of Hampstead’s hill consists of this Bagshot sand through which water passes easily. The next Claygate Beds layer provides a semi-permeable barrier that checks the water and sends it out as springs at the boundary zone – for example those on the meadow below Kenwood House – and provided the water for the many surface wells around Hampstead and the rivers of north London – the Fleet, Tyburn and Westbourne rivers. Claygate Beds however do let some water pass through.

The next layer of London clay though is much more impermeable. Water does not pass through it, except via sand partings left behind by older streams and springs, so some further springs will still be found at this boundary zone. [Eric Robinson has written an explanation of the local geology.]

Building houses on clay: Water in clay

The Georgians and Victorians built many terraces throughout London. They knew of clay’s characteristic of swelling when wet in winter and shrinking in summer. This roughly 7% change in volume means an individual house – provided it has uniform foundations – will most likely move up and down uniformly and avoid subsidence, the plasticity of lime mortar absorbing any slight movement.

Terraces stretch over a wider area so the Georgians and Victorians in their wisdom generally floated them on the surface of clay with small shallow fixings so that the whole terrace went up and down with the seasons but didn’t show signs of subsidence. Lathe and plaster internal walls also acted like relatively unfixed plasterboard within their framework of wooden skirting board / wainscot and ceiling mouldings, keeping movement isolated to these hidden joints and preventing cracking of the exposed walls

Add on an extension however, with different foundations and rigid cement mortar, and differential subsidence can occur. Dig out a basement and several things can happen. Fixings into the deeper denser clay mean that part of the building moves less than the rest, again resulting in differential subsidence. The modern basement will also be made completely water impermeable. This is fine for the basement, however it will dam up any water previously passing through sand partings causing lakes to form underground. This occurred behind the Royal Free Hospital that was responsible for the major subsidence of St Stephen’s Church; vibration from the piling speeding up the slide down the hill lubricated by the water

If the effect of a basement is to constrain flowing ground water into narrower gaps, perhaps under neighbouring buildings, this can cause sand to wash away so that drains or foundations lose their support, or cause the surrounding clay to swell considerably more than the usual seasonal change and attract tree roots. The tree roots will help as they reduce the effect of the water, however if they are then blamed by insurance companies for causing subsidence cracking and removed, the situation can be made much worse.

The London Tree Officers Association has been alerted to the effect of leaking drains by their work with the engineer Jeremy Johnson, and are gathering data to investigate this further. Jeremy Johnson has provided us with an article that explains how leaking drains cause subsidence. We also believe that geology can have a similar effect in Hampstead when water in springs and sand partings is diverted and starts causing trouble. Diverted water can also mean diversion away from trees: they have a difficult enough time surviving in the lead up to climate change. We are worried that some will die

Subsidence

Our advice when subsidence cracking becomes evident is first to consider whether it is worth worrying about. Insurance companies report that they do not consider 40% of claims: those claims made for cracks of a millimetre or less. Householders should consider this, since the mention of subsidence increases premiums. It has been usual in the past to merely apply polyfiller and a new coat of paint if the cracks concern you. This practice is much cheaper than approaching your insurance company.

If the cracks are significant and not known to have occurred before, then the source of leaking water or the cause of excess water should be sought.

This may be a down pipe whose joints have come apart, or a soil pipe underground going to or from a manhole. Nearby basement or foundation work will have altered ground pressures which may reduce the support for such pipes causing them to crack or joints to come loose. Trees will expand their trunks and the large roots just below the trunk over time. This can push on pipes placed very close to tree trunks or trees that have been planted over them. It makes sense to move the pipes out of harms way; preferably not to plant trees right over pipes in the first place.

It is a fallacy that the small fibrous tree roots sometimes found inside drainage pipes are able to break pipes open. Roots don’t know the water is there until the pipe is already cracked. In Hampstead this is much more likely to be caused by the local hydrogeology with its several boundary zones and zones of relatively unstable land on slopes, or the effect of basement digging on ground pressures. Thames Water may be able to tell you of local drain pipes that have burst or are leaking. These should be rapidly mended to stop more sand being washed away or clay expansion alleviated as soon as possible. You will then need the trees to re-balance the situation.

If you have signs of subsidence and heave in your road with pot holes and an undulating surface then you or your neighbours will probably recall the basement work or a burst water main that preceded this. Looking down pot holes can reveal the existence of quite large cavities that have formed under roads. Interference in the ground water can contribute to both subsidence (slow wash-out of material) and heave (clay swelling). Remember too that swimming pools can be dug into the floor of a basement so they make the basement – and thus the block to ground water flow – several meters deeper.

Swimming pools built into clay on a slope are also notorious for eventually cracking. Slow leaks of pool water will cause clay expansion/heave and have been known to lubricate the movement of buildings down clay slopes. Basement boundary walls on slopes have to take the weight of the hill above them if there are local slip surfaces in the clay made by glacial movement during the last ice age. If local vibration from machinery and diverted ground water is present, this will shake and lubricate this slippage. This is partly what gives us concern for basements built in hilly Hampstead with its springs and geological boundary zones.